UMBRIAN-ETRUSCAN ORIGINS AND THE ROMAN AGE

Between legend and archaeological ruins, Todi origins still remain shrouded in mystery. According to tradition, the town was founded in 2707 B.C. by the Veii-Umbrian tribe. It is said that, while the men were bivouacking after having started the building works downstream on the Tiber banks, a mischievous eagle took their tablecloth away, dropping it on top of the hill behind. The sign was welcomed as a message from God, the town was built there and the eagle became the emblem of the town, reproduced in numerous effigies.

Besides fantastic stories, the archaeologists could spot the core of an original village, dating back to the 8th-6th centuries B.C., inhabited by farmers and shepherds. It was soon subjugated by the nearby Etruscans. The same name of the town proves this. From the Etruscan “Tular” or “tulere” meaning “border”, came the following Roman name Tuder, the Medieval Tudertum and finally the vernacular Tode, up to the current name: Todi, which inhabitants are called Tuderti or Tudertini.

The first walls, built between the 3rd and the 1st centuries B.C., are attributed to the Etruscans.

In 89 B.C. Todi gained the status of Roman municipium and underwent an urban-architectural development. Its core was Piazza del Popolo (People’s Square), the ancient Forum where the Capitolium (currently the Cathedral) and the public buildings would stand out, but almost nothing remains. The echo of the flourishing Roman Age is still enshrined in the underground tunnels of the Square, in the Nicchioni and in the names of the roads recalling the ancient town gates: Porta Aurea, Porta Libera and Porta Fratta in the South-West, Porta Catena and Porta Marzia in the South- East.

THE MIDDLE AGES AND THE COMMUNES

The Fall of the Western Roman Empire involved Todi, as well, which underwent the Barbarians’ raids. Firstly the Goths who were pushed away by the providential intervention of St. Fortunato, Bishop and Patron of the town. Then the Longobards who split the conquered territory in dukedoms and turned into authoritarian feudatories, constantly fighting against the local lords. The most popular families involved in the battles were the Counts of Montemarte, the Arnolfi and the Atti.

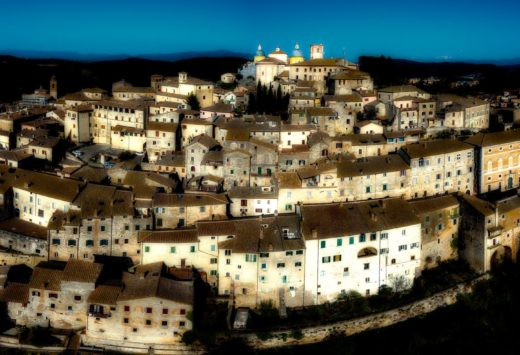

Only since the 13th century, the town has enjoyed the best time of its history: the town walls were expanded up to embracing the two surrounding buttresses on the Northern and Southern sides, delimited by the monumental gates of Porta Orvietana, Porta Perugina, Porta Romana and Porta Amerina. Therefore, the town took its final shape which has remained intact almost up to the present day.

During those years, Todi expanded its authority over the nearby towns of Amelia and Terni which started paying tribute to the town. It exercised its power over the Papal feuds of Alviano and Guardea, took the power of the Nera valley away from Orvieto and started to establish important political and commercial relationships with Perugia.

In 1236, the wealthy town gave birth to Jacopo de Benedetti, renowned as Frà Jacopone da Todi, the epic poet of the Passion of Christ and the author of some among the most popular Laudi of the Italian vernacular literature.

Jacopo was a notary who had married Vanna, a noble woman who died approximately one year later, crushed by the rubble of a collapsed floor while she was dancing at a ball. On that occasion, the future friar saw the cilice on his wife’s thigh. After a long period of spiritual crisis and pilgrimages, he converted and took vows. His remains are kept in the crypt of St. Fortunato Church and are currently a favoured destination for pilgrims and tourists.

FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO MODERN TIMES

When Boniface VIII was elected as Pope (1294), Todi underwent a further economic and political development. In fact, the new Pope began a diplomatic activity, really appreciated by Todi Ghibellines. He took direct control of the town ecclesiastical heritage from the Rector who was allied to the Guelphs. With the help of the Catholic Church, the town managed to seize Montemarte Castle, a point of contention between Todi and the rival Orvieto, for a long time.

The crisis began a few years later when Boniface VIII died, in the 14th century, and Todi fell into Charles IV’s hands who assigned it to the new Pope and to a large number of Princes and Captains. Among them, Malatesta da Rimini, Biordo Michelotti and even Francesco Sforza.

Only in the 16th-17th centuries Todi underwent a short stage of resumption. Bishop Angelo Cesi’s last architectural and urban interventions are ascribable to this period; gems such as the Fountain of the Rua or Cesia Fountain (named after him), the Crucifix Church and the masterpiece of the Church of St. Maria della Consolazione, attributed to Bramante, set forth the synthesis and conclusion of the urban outlining which would have developed with small works only, during the following centuries.

The town has settled by now. Different ages have blended harmoniously and without contrast.

In the latest decades, construction has involved outskirts, only, leaving intact the Old Town, with its connotation of ancient and rural centre.